Another place: sport's global, local future

Whether in Wrexham, Wembley or shared online spaces, sport is facing trends that will reshape its communities.

From here to there

Where will the sports industry be ten years from now?

The whole thing is braced for irresistible change, and the compound effects of what’s changing already.

But where will it be?

About a week ago, I was at London’s Kia Oval for the superb tenth edition of SportsPro Live, which ended with an on-stage discussion about the shape of the decade to come.

SportsPro CEO Nick Meacham and editorial director Michael Long were joined by Laura Williamson, deputy editor of The Athletic – a digital-native media company which courts a global audience with specialised local coverage.

It was a wide-ranging chat but my attention snagged on one exchange in particular.

To paraphrase: in the next ten years, Long said, sports organisations must understand their local effects and responsibilities amid a sustainability crisis and spiking living costs.

But, Meacham countered, the consumption of sport is only getting more global, and its opportunities for growth and relevance lie in mastering turbulent media conditions and a whole range of emerging digital spaces.

The reality, inevitably, lies somewhere in the middle. There’s no hiding from the fundamental distortion of the media rights model or the idea that fewer and fewer people encounter sport for the first time through a live event or TV broadcast.

Among the exhibitors at SportsPro Live was Beyond Sports. Part of Sony’s Hawk-Eye Innovations group of companies, it produces data-led digital recreations of real-world sport in real time. Earlier this year, it trialled a ‘live’ NHL game in the world of Disney animated series Big City Greens, and it recently agreed a partnership with the league to try something similar in the massively multiplayer game Roblox.

Concepts like that abound. But so too do examples of creative attempts at rethinking sport’s place in its local environment, restoring frayed ties or rewiring ideas to be compatible with a different system.

There is a tension here that has existed for decades. The forces acting on it, though, come from more directions all the time.

The shop around every corner

No one can have watched 1998’s You’ve Got Mail at any point in the last 15 years – at least – without detecting the dramatic irony. The owner of a New York children’s bookstore faces down the CEO of a giant chain, Fox Books, desperate to avoid becoming the latest victim of an insatiable retail empire. Meanwhile, the two develop a warm but anonymous romantic relationship over email, having met in an internet chatroom.

Both their businesses, of course, would have been vulnerable just a few years later to the then-novel communications technology that brought them together. Online shopping in general, and Amazon in particular, squeezed out not just charming little boutiques but the brick-and-mortar behemoths that used to land on top of them.

More recently, though, there has been an unexpected twist. First came a resurgence in the prevalence of independent bookshops, which reached a ten-year UK high in 2022 before coming under threat from rising energy costs and inflation.

And those fallen giants of high-street retail have taken notes. In the US, Barnes & Noble is reinventing itself under the ownership of the hedge fund Elliott Advisers and the leadership of British bookstore veteran James Daunt.

Its focus is on localisation, smaller footprints with cosier layouts, the celebration of emerging authors and more personal curation by staff. This follows the playbook Daunt established in the UK with Waterstones and Hatchards – also owned by Elliott – and his own Daunt Books.

“The trouble when you have Amazon as a competitor is that you have to give people a reason to come into your bookstore. It has to be interesting and engaging. And for books, that isn’t a single defined proposition. You actually end up with a blended average of everything that satisfies no one.

“There was also a misunderstanding that it was simply about racking up the books, as many titles as possible, so that if you woke up in the morning and wanted a book, you drove to your bookstore, you walked in, you asked a bookseller, they took you to the book, you picked up the book, you bought it, and you went away. Well, Amazon does all of that process dramatically better.

“What you had left and forgotten about is that people come to bookstores to enjoy themselves. They come to meet other people, they come for the social experience, and they come to browse and look at books. It’s a very richly textured, actually emotional engagement that customers have with bookstores, and independent booksellers do that brilliantly. They understand their customers, they curate for their customers. The big chains had simply stopped doing that — well, I don’t think they’d ever done it, in truth — and therefore the business was failing.”

In music, buoyed in part by the continued comeback of vinyl sales, HMV is pursuing its own turnaround on similar terms. It has returned after a four-year absence to a flagship store on London’s Oxford Street, promising a “fan-focused pop culture offer” based on events, artist appearances and more carefully selected products.

Naturally, however enlightened these companies may look next to their 90s and 2000s selves, independents don’t want to cede the cultural power of these spaces altogether. Some see a way to harness the convenience and network effect of an Amazon-style service and support smaller businesses – like Bookshop.org, an online sales portal that passes revenues on to a local UK outlet of the buyer’s choosing.

Welcome to Wrexham, twinned with Anytown

Hollywood, in the popular telling, is a place people come to from somewhere else.

By now, the opening beats of the Wrexham AFC takeover pitch are familiar. Rob McElhenny is of Hollywood but from Philadelphia, where the sun shines less than you might have heard. Humphrey Ker, a writer and actor on McElhenny’s videogame comedy Mythic Quest, introduced his sometime boss to the Netflix documentary Sunderland ’Til I Die, about the decline, stagnation and defiance of a former Premier League team in a post-industrial town.

McElhenny, enraptured, wondered if he could help tell that tale in reverse – building a slice-of-life TV series around a football team on the rise. He slid into the DMs of Ryan Reynolds – an A-lister and skilled entrepreneur – and the duo contracted Inner Circle Sports LLC to find the right opportunity.

Wrexham was the pragmatic choice for a fairytale. More than a decade removed from English Football League status, the third-oldest professional team in the world were a sleeping giant who could benefit from the right backing. Promotion and relegation have been known to spook American investors in the upper reaches of European football but further down the pyramid, they offer a clear route to a return on spend.

And Wrexham have spent: last season’s accounts saw income rise to nearly £6 million but losses hit £2.9 million. The ownership vehicle, The R.R. McReynolds Company LLC, loaned the club £3.67 million and invested £1.2 million in the form of shares.

That outlay has added up to a significant competitive advantage in the fifth tier of English football – one that Ker, also speaking at SportsPro Live last week in his capacity as Wrexham’s executive director, has said the owners were keen to reinforce by getting the right sporting structure in place early.

Meanwhile, the takeover process brought McElhenny and Reynolds into early and frequent contact with the Wrexham Supporters’ Trust, who controlled the club prior to their arrival. £2 million was spent buying back the team’s Racecourse Ground home, restoring an asset that is so often stripped away from less fortunate clubs by less salubrious owners. Further investment is earmarked to revamp the stadium and training ground, refresh the youth academy and drive the women’s team towards the elite.

None of this really lands without that granular local commitment. McElhenny has a producer’s eye for setting as character; a storyteller’s sense of the personal as universal. If communities in Sunderland are like communities in Wrexham, and in Philadelphia, then there must be something about them that connects with places like that everywhere. And the owners, clearly, have been swept along on the emotional currents they unleashed in North Wales.

Still, as Financial Times sports editor Josh Noble puts it: ‘This is global capitalism, back to revive one of the many towns it left for dead.’

The plan only scales with a worldwide media and merchandise footprint. The FX series folds into Disney+ and pairs with ESPN. When viewers overseas began showing an interest in watching games live, Wrexham made no doubt of their desire for a more liberal National League streaming policy. Partnerships with TikTok and Expedia follow the owners’ profiles and evidence of an outsized audience dropping in.

At this moment, resources and ambitions and worldviews all match up neatly. The real complexity is only just setting in. How far can this go? Where does the backing come from for the more expensive challenges ahead? Does Disney see an IP opportunity in this beyond the documentary? Or is the exit a stable, regionally popular side who are looked on fondly from afar?

In short, what kind of a club will Wrexham become?

Success changes every underdog story – as Philadelphia’s own Rocky Balboa can attest. If Wrexham crane their necks up to the Premier League they’ll see a couple of clubs, Brighton and Brentford, who have carried their communities to the very top with smart, incremental adaptation. But it’s a hard road, paved with conflict and compromise.

“As I’ve told the guys from the start — there will come a time where we’re in the Championship and we draw three games in a row, and one of you will get called a c**t in Manchester Airport by a Wrexham fan,” [Ker told the Financial Times].

“Eventually, the most valuable story in football will be their comeuppance, it’ll be their downfall. But that’s just part of life and we’ll come to it when it arrives.”

In the arena

One way or another, sport takes the shape of its surroundings.

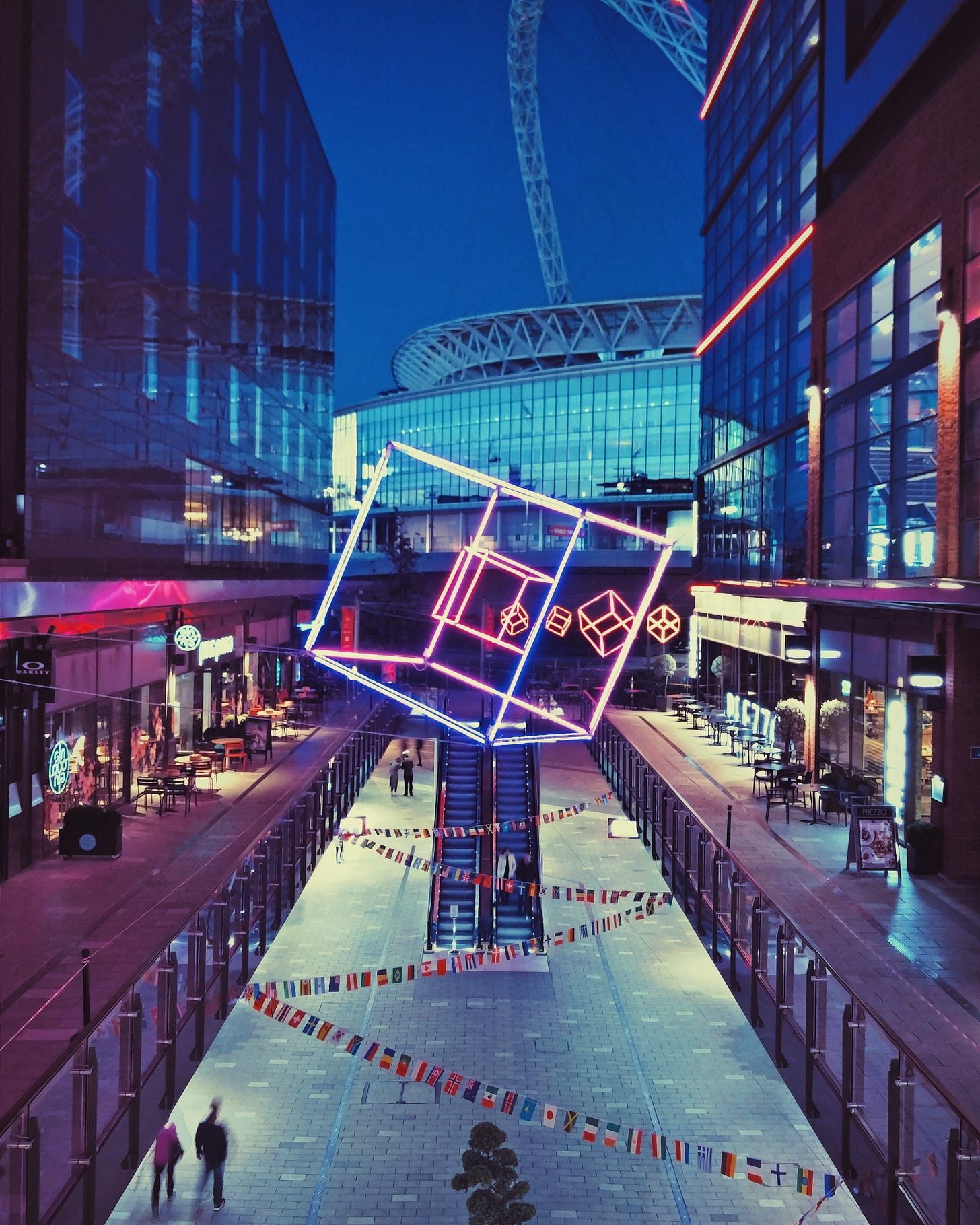

100 years ago last week, on 28th April 1923, Wembley Stadium hosted the FA Cup final for the first time. It forever altered the destiny of a London suburb still barely emerging from its agricultural past. Yet the subsequent transformation has resulted from a complex set of factors way beyond football, music or rugby league. What was once the Empire Stadium now sits in the UK’s second-most culturally diverse borough.

That original structure was knocked down in 2000 and its replacement, if we’re being honest, elicits complicated feelings among fans, despite its venerated status and high-end trappings. Its relationship with the local area is also evolving.

Developer Quintain has spent around £2.5 billion on the adjacent plot to create a gigantic residential and leisure complex. As a consequence, Wembley Park is busier and buzzier than ever before – even if, with its 6,000 ‘built-to-rent’ homes, it looks to some critics like regeneration on a lease.

This type of revitalisation project is of a piece with what has happened across London at Battersea Power Station – the reimagining of local landmark as luxurious entertainment hub. It is interesting to wonder what vision the Football Association, the stadium’s owner, might have sketched at this scale on a blank piece of paper.

Big infrastructure projects have an obvious impact – creating jobs, educational opportunities and ‘year-round entertainment and leisure destinations’. But they are big and costly and cumbersome, and they don’t get to happen very often.

The living is done in between. Cities and towns are redefined not just by construction but the smaller adjustments to technological change, societal trends, punishing economic cycles and the need for a greener perspective.

In encouraging participation and active lifestyles, governing bodies are grappling with how to fit their sports into urban spaces and how to overcome the barriers of travel and access that exist elsewhere. Some cities and governments are designing sports strategies that try to bring health, sustainable transportation and commercial goals in line.

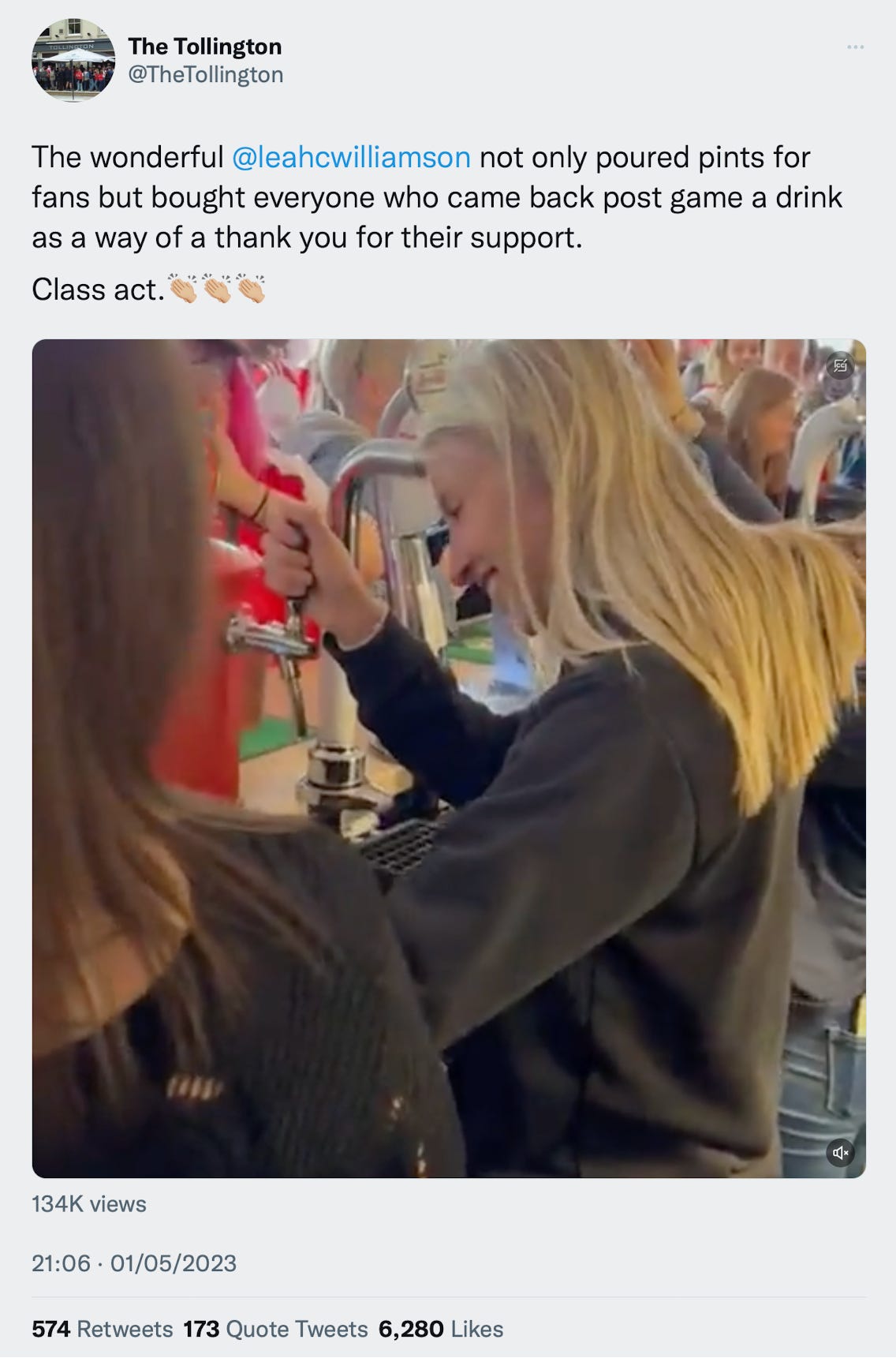

And teams are becoming more thoughtful about their interactions with their neighbours, both in how they deliver social initiatives and promote a thriving local economy. In the Premier League, clubs like Arsenal and Liverpool have made fans aware of small businesses that might become part of their matchday – whether they are at their first game or they go every week.

It may be that these are ideas that can be repurposed for fan groups in other parts of the world, or that teams find a different role to play in high streets that drift from retail towards other functions and experiences.

Sport, on some level, is about optimism and community. How that can take it somewhere better is always open to debate.

Eoin Connolly is a sports industry writer, editor and presenter. He is also the editorial director at Trippant.