Sport, entertainment, and everything in between

Sport is grappling with its place in infinite media space. So where does it ground its identity?

Making matter

The last few years have been a good time, and a tricky time, to be in the business of things people care about.

This is not an original or profound observation. But the thought came back to me around a week ago, as I worked my way through a third or fourth podcast about a single episode of Succession.

There is so much more space, if you can fill it, for everything: more conversation, more celebration, more community, more specialist expertise. More to get lost in as a consumer; if you’re a creator, more ways to disappear.

It’s a reality that presents two basic sets of challenges. One is practical and commercial. How do you reach an audience with the resources you have available? Are you maximising the opportunities of scale or the possibilities of your niche?

The other goes deeper, towards questions that are less philosophical than they sound – questions that sport, for various reasons, has not always stopped to ask in the past. What’s the difference between something that gets your attention and something that holds it?

There are stories, and then there are stories that stay with you, urging you to sit with them, digest them, gather every scrap of evidence you can find about the author’s intent. There are pastimes that are not just fun but so absorbing they envelop your life – maybe even your identity.

Sports organisations are making sense of their place in a media and cultural environment where everything feels looser, with the guard rails removed. It is a search not just for relevance, but resonance.

Back to first principles

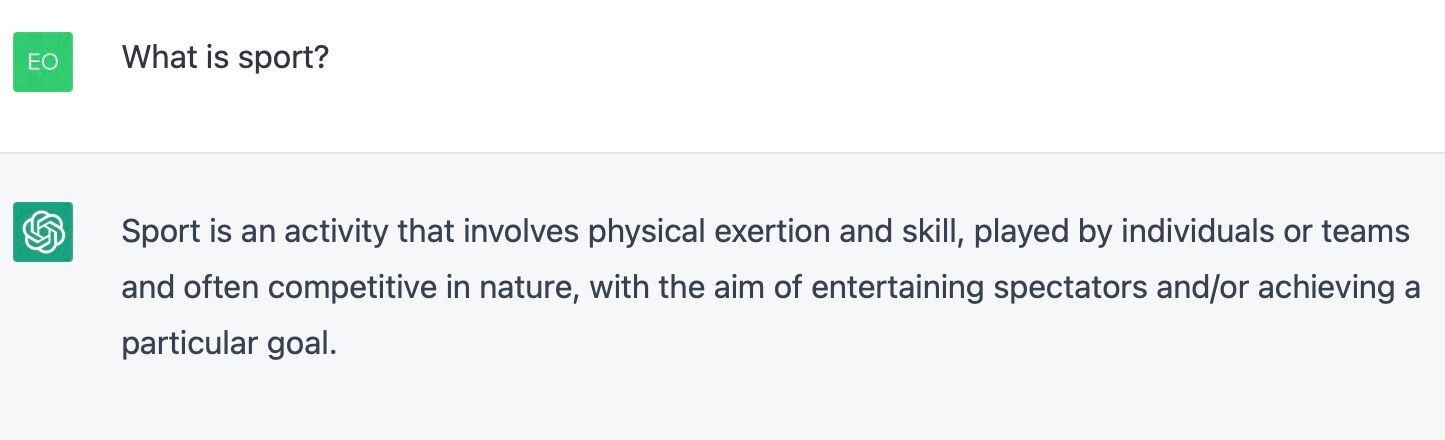

Here’s something I asked ChatGPT.

Not quite as compelling as LinkedIn led me to expect. But then, I wasn’t really asking the right question.

Earlier this year, six members of the Florida Institute of Technology (FIT) men’s rowing team took their school to court. They believed a cut to their programme constituted an unusual breach of the Title IX regulations on how sport is funded in the US education system – in that FIT had limited opportunities for male student-athletes by not providing them the same amount of money as it did for women.

FIT argued that the plaintiffs had overlooked the existence of a men’s esports team in their calculation. But in February, US District Judge Carlos Mendoza ruled in favour of the rowers. Competitive video gaming, according to the outcome of Navarro v. Florida Institute of Technology, is not a sport.

Pretty definitive, right? But outside of that context, what does it change?

Darts is defined as a sport by every UK sports council. Bridge is not, but it’s still been played at the Asian Games. And I doubt your PE teacher would have let you do either of them instead of cross country.

Sometimes it matters that sport is sport, particularly in integrity and governance. But some things that sport achieves can also be found in other genres – from music to gaming to format TV. It is worth asking how the future is being shaped there, too.

Squaring the circle

Professional wrestling: you know it’s fake, right?

The old playground standard – a question asked by those who probably didn’t get it to those who probably didn’t care.

WWE has been called a lot down the years. ‘Sports entertainment’. ‘Scripted reality’. ‘The WWF’. And ‘fake’, as far as I can tell, is an epithet fans wear like a stage slap across a waxed chest. It barely leaves a mark.

Their enjoyment is real enough. So is the money. Earlier this month, the giant sports and entertainment agency Endeavor bundled WWE into a $21 billion venture with its unscripted combat sports juggernaut, the UFC. An all-stock agreement valued WWE at $9.3 billion.

By now, there is plenty of smart analysis of that deal elsewhere. Suffice to say, Endeavor has seen in WWE the same qualities that first inspired it to buy into the UFC back in 2016: the same hegemony over talent and fandom; the same potential to take that talent to different audiences through Hollywood connections. There is a long and obvious history of WWE stars building movie careers, and a beaded curtain between the two promotions as well.

WWE has grown quickly and consistently for 40 years, counting out competitors while staying alert to lucrative opportunities in media rights and sponsor integration. It leaned on a dominant market position and the certainty of its planned outcomes to be innovative or archly pragmatic – whichever it paid to be at the time.

Millions of followers are not just unmoved by that question above, they see it as part of the escapist appeal – of a piece with the spectacular athleticism, the high-end production and the leathery melodrama.

There is this thing that WWE does at its best, something it has in common with most of the big sports and entertainment successes of our young century. It makes stories that people want to be part of.

Playing pretend

Kayfabe is the fib that makes professional wrestling possible, perched somewhere on a spectrum between the theatrical suspension of disbelief and the irrational lifelong investment of sports fandom.

It has some properly fascinating implications and effects. And it’s also interesting because of what WWE impresario Vince McMahon has done with it – updating it for our always-on, multi-channel epoch.

Abraham Joseph Riesman, author of Ringmaster: Vince McMahon and the Unmaking of American, explained the distinction in a February essay for the New York Times.

Old kayfabe was built on the solid, flat foundation of one big lie: that wrestling was real. Neokayfabe, on the other hand, rests on a slippery, ever-wobbling jumble of truths, half-truths, and outright falsehoods, all delivered with the utmost passion and commitment. After a while, the producers and the consumers of neokayfabe tend to lose the ability to distinguish between what’s real and what isn’t. Wrestlers can become their characters; fans can become deluded obsessives who get off on arguing or total cynics who gobble it all up for the thrills, truth be damned.

In Riesman’s argument, neokayfabe has a role in everything from the corrosion of public discourse to the ascent of one recently arraigned former US president.

Whatever its ramifications, there’s no doubting McMahon’s dedication to the bit. For decades, away from the boardroom, he has portrayed an outsized version of the villain that fans of other sports plainly consider their leaders and administrators to be.

The more McMahon wrote this version of himself into WWE’s stories, the more he became a lightning rod for whatever people did not like about his product. And that only made his heroes more compelling when they tossed him out of the ring.

WWE became a very effective, very creative, sometimes pretty ruthless business. But playing all this out in public has its complications. McMahon has explored this persona to its blurry limits.

Last year, in absolutely real life, he was almost forced out over a scandal involving hush-money payments to former employees amid allegations of sexual misconduct and infidelity. After surviving that episode to return as executive chairman in 2023 – a position, incidentally, he has consolidated with the Endeavor/UFC merger – McMahon adopted a pencil moustache that makes him look like a cross between Walt Disney and himself sneaking over a border in disguise.

But in his absence, some WWE fans have noticed something else. They’ve been having more fun: a sensation they attribute to fresher creative direction under CEO Nick Khan and former WWE champion turned chief content officer Paul Michael Levesque, McMahon’s son-in-law who wrestled as Triple H.

That’s the next wrinkle. Plotting something out in public – the progress of a football team, or the next entry in the Marvel Cinematic Universe – can be a magnetic process, but participation brings scrutiny and debate.

Redrafting the story of sport

The late film critic Roger Ebert described the movies as ‘a machine that generates empathy’.

Sport can do that. It can also reinforce community, produce a spectacle, or stimulate physical and economic activity.

And historically, the theory went, those qualities flowed from one another. You design a well-balanced contest, run it safely and fairly, and provide access to opportunity. If you wind up with the best against the best, the result is likely worth watching.

The competition came first and the meaning followed. Whatever human drama or communal awakening existed in sport was found there, not put there. That sets it apart from the creative industries, where stories are seeded with intent, but has sometimes left it less prepared for making something new or retooling what is there for a different era.

The most successful new sports properties of the last generation, the aforementioned UFC and cricket’s Indian Premier League, were both based on novel formats but had that notion of best versus best at their centre. The presentation and positioning grew from that.

But not everything has been established on that basis. For leagues created to unlock new audiences, the right throughline can prove more elusive. It can be harder to connect with the purpose and easier to see the joins. The underlying motive is telegraphed.

LIV Golf is an interesting example: one of the most and least talked-about competitions of the last 18 months. As a news story, it’s compelling – wrapped as it is in the sense that geopolitics is not some arms-length abstraction handled by professionals. Setting the many moral and ethical considerations aside, though, reaction to the tour itself has been a smorgasbord of meh.

That could change. The sheer financial weight of the enterprise could barrel into an irresistible force that gathers a fractured sport on its run. Who knows: it may only take an episode like Brooks Koepka beating Jon Rahm at the Masters, instead of the other way round, to set that in motion.

But for now, how many are talking about the golf? And how many are asking: “Would you take that money?”

Why something matters, and who it matters to, really counts. Influencer boxing makes sense to fans of the influencer, rather than the boxing. The Kings League, Gerard Pique’s quirky seven-a-side football experiment, hooked its audience with the mystery of a masked player, Enigma. His identity – the out-of-contract Nano Mesa – was less glamorous than rumoured but a youthful, Twitch-native fanbase made that speculation their own.

In the end, those newcomers can fail and try again. The old guard have a little more at stake. The right adaptations can revitalise an enduring favourite, the wrong ones hollow out its emotional core.

The secret about sport is that on some level, it is every bit as confected as The Great British Bake Off. Yet millions hang on the weight of every souffle.

There’s not much reason for any of this to matter – until there is. Working out how that still happens is the biggest test to come.

Introducing Outlines: Notes from the boundaries of sport, culture, politics and tech

Thanks for reading this first post from Outlines. It’s great to get started.

And I’m excited to see where it all goes. Right now, this project is itself an outline – a sketch of a concept that will emerge over time. I’ll play around a bit with form and content: some entries will be longer reads like this one, some will be punchier, or denser, or more scattered. This is an ideal place, too, to share and engage with brilliant work I find elsewhere.

Look out for the next edition in a regular slot on Tuesday, when I’ll also be off to the Kia Oval for the tenth edition of SportsPro Live. I’m looking forward to enjoying what my old team have put together and struck by the years of change reflected in the agenda – including a session on Wrexham’s Hollywood story.

In my time covering the sports business, I’ve always been intrigued by the cultural and commercial influences flowing downstream from other industries, and by the sporting trends that bubble up elsewhere. There’s a lot in each that explains the others: through media, storytelling, community and social dynamics and the economy of fandom.

It will be fun to wade through it all.

Eoin Connolly is a sports industry writer, editor and presenter. He is also the editorial director at Trippant.